How do state estate and inheritance taxes work?

Estate and inheritance taxes are taxes levied on the transfer of property at death. State and local governments collected a combined $6.7 billion in revenue from estate and inheritance taxes in 2021.

An estate tax is levied on the estate of the deceased while an inheritance tax is levied on the heirs of the deceased. Only 17 states and the District of Columbia currently levy an estate or inheritance tax.

How much revenue do state and local governments raise from estate taxes?

State and local governments collected a combined $6.7 billion in revenue from estate and inheritance taxes in 2021, or 0.2 percent of general revenue. New York collected $1.5 billion in estate tax revenue in 2021, the most of any state, but that was still less than 1 percent of its state and local general revenue. Pennsylvania was the only other state to collect more than $1 billion in estate or inheritance tax revenue. In total, 11 states collected more than $100 million in estate or inheritance tax revenue in 2021.

Some states that have repealed their estate tax still collected a small amount of estate tax revenue in 2020. For example, Ohio repealed its tax in 2013 but collected $2.6 million in estate tax revenue in 2021 from taxes levied before repeal. Twenty-three states did not collect any estate or inheritance tax revenue in 2021.

How much do estate taxes differ across states?

In 2023, 12 states and the District of Columbia levy an estate tax and six levy an inheritance tax. Maryland levies both.

New Jersey and Delaware both repealed their estate taxes in 2018. New Jersey still maintains its inheritance tax, though. Iowa passed legislation in 2021 that will phase out the state's inheritance tax until it is fully repealed in 2025. Most other states without an estate tax eliminated their tax soon after changes were made to the federal estate tax in 2001 (see the section on federal changes below).

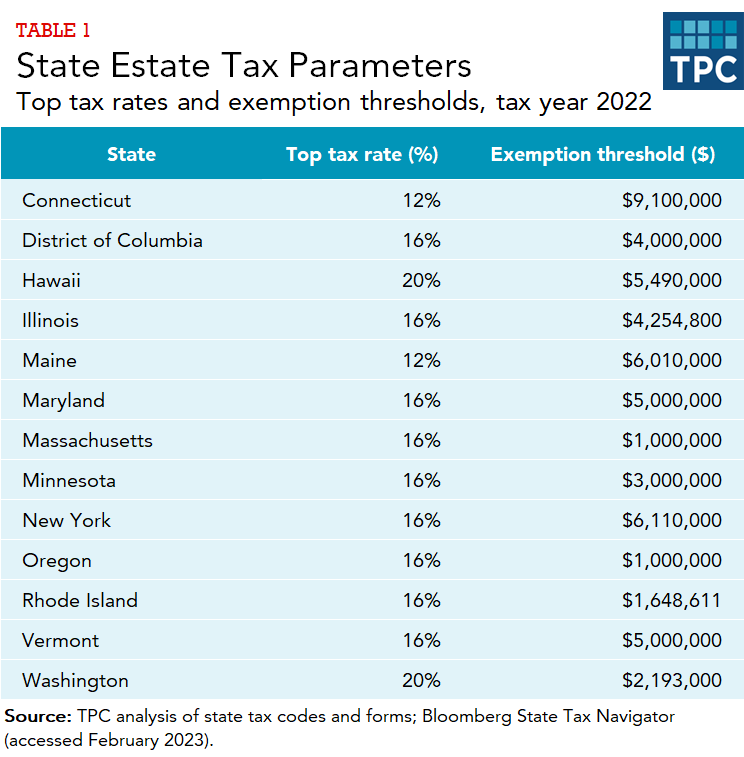

Like the federal estate tax, all states that tax estates offer an exemption that excludes most estates from taxation (table 1). The lowest state exemptions in tax year 2022 were $1 million in Oregon and Massachusetts. The highest exemptions were in Connecticut ($9.1 million), New York ($6.11 million), Maine ($6.01 million), Hawaii ($5.49 million) and Maryland and Vermont (both $5 million).

Most states have a progressive rate structure (for example, see New York's tax table) with a top estate tax rate of 16 percent, a relic of the previous federal estate tax credit system (see the next section for more on the old federal credit and how it affected state estate taxes). However, Connecticut (12 percent), Hawaii (20 percent), Maine (12 percent), and Washington (20 percent) have set their own top estate tax rates.

States with inheritance taxes (Iowa, Kentucky, Nebraska, Maryland, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania) also use various exemptions and tax rates. For example, in New Jersey, surviving spouses, parents, children, and grandchildren are all exempt from the tax. However, a brother, sister, niece, or nephew can pay a tax rate of up to 16 percent on the inheritance. Meanwhile, in Pennsylvania, a surviving spouse is exempt, an adult direct decedent pays a 4.5 percent tax, a sibling pays a 12 percent tax, and other heirs pay a 15 percent tax.

How did a 2001 federal law change upend state estate taxes?

Before 2001, all 50 states and the District of Columbia had an estate tax because the federal estate tax provided a dollar-for-dollar credit of up to 16 percent of the estate’s value for state estate taxes. Thus, states could raise revenue without increasing the net tax burden on their residents by linking directly to the federal credit, and all states did so by setting their estate tax rate equal to the maximum federal credit.

However, federal tax changes in 2001 (the Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act), phased out the federal credit in 2005, replacing it with a less valuable deduction. Because state estate taxes were linked to the federal credit, this meant all state estate taxes would disappear if states did not act. In response to the federal change some states decoupled from the credit and created their own state estate tax, some states repealed the tax outright, and others did nothing (effectively ending the tax).

Updated January 2024

Auxier, Richard. 2019. The Death Tax Isn’t So Scary for States. Washington, DC: Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center.

Francis, Norton. 2012. Back from the Dead: State Estate Taxes After the Fiscal Cliff. Washington, DC: Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center.

Interactive data tools