What are tax expenditures and how are they structured?

Tax expenditures are special provisions of the tax code such as exclusions, deductions, deferrals, credits, and tax rates that benefit specific activities or groups of taxpayers.

The Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act of 1974 defines tax expenditures as “revenue losses attributable to provisions of the Federal tax laws which allow a special exclusion, exemption, or deduction from gross income or which provide a special credit, a preferential rate of tax, or a deferral of tax liability.” These provisions are meant to support favored activities or assist favored groups of taxpayers. Thus, tax expenditures often are alternatives to direct spending programs or regulations to accomplish the same goals. The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and the Congressional Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) each year publish lists of tax expenditures and estimates of their associated revenue losses. The US Department of the Treasury prepares the estimates for OMB.

The key word in the definition of tax expenditures is “special.” OMB and JCT do not count all exemptions and deductions as tax expenditures. For example, the agencies do not count as tax expenditures deductions the tax law permits to measure income accurately, such as employers’ deductions for employee compensation or interest expenses. Similarly, OMB and JCT do not count standard deductions that differ by filing status as tax expenditures on the theory that exempting a basic level of income from tax and adjusting for family composition are appropriate in measuring a taxpayer’s ability to pay.

More generally, both the decision to count a provision as a tax expenditure and the measurement of its size require that OMB and JCT define a normative or baseline system against which some provisions are exceptions. Both agencies include in the baseline system provisions that allow tax rates to vary by income and that adjust for family size and composition in determining taxable income. OMB and JCT also allow for a separate tax on corporate income. The baselines of the two agencies do differ in some details, however, which contribute to modest differences in their lists of provisions and their estimates of revenue losses.

Tax expenditures take different forms

Deductions and exclusions reduce the amount of income subject to tax. Examples are the deduction for mortgage income on personal residences and the exclusion of interest on state and local bonds. Deductions and exclusions typically reduce tax liability more for higher-income taxpayers facing higher marginal income tax rates than for lower-income taxpayers in lower rate brackets, since a deduction is worth more at a higher rate and higher-income taxpayers often spend more on the subsidized item.

A special category of deductions, called itemized deductions, is valuable only to taxpayers whose sum of itemized deductions exceeds the standard deduction amounts available to all tax filers. The largest itemized deductions are those for home mortgage interest and charitable contributions. In tax year 2017, about 27 percent of tax units (tax returns plus nonfiling units) claimed itemized deductions. Following the increase in the standard deduction and new limits on deductibility of state and local taxes from the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, only about 10 percent of tax units will claim itemized deductions in tax year 2024. However, an itemized deduction claimed mostly by higher-income taxpayers is not necessarily unfair, if the standard deduction is worth more to lower-income taxpayers than claiming the deduction. Some itemized deductions may still be objectionable because they are inefficient or inappropriate as a matter of policy.

Credits reduce tax liability dollar for dollar by the amount of credit. For example, the child tax credit reduces liability by $2,000 per child for taxpayers who are eligible to use it fully. A special category of credits, called refundable credits, allows taxpayers to claim credits that exceed their positive income tax liability, thereby receiving a net refund from the Internal Revenue Service. The major refundable credits are the earned income tax credit and the health insurance premium assistance tax credit, which are fully refundable, and the child credit, which is refundable for those with earnings above a threshold amount.

Some forms of income benefit from preferential rates. For example, long-term capital gains and qualified dividends face a schedule of rates ranging from 0 to 20 percent, compared with rates on ordinary income, which range from 10 to 37 percent.

Finally, some provisions allow taxpayers to defer tax liability, thereby reducing the present value of taxes they pay, either because the taxes are paid later with no interest charge or because they are paid when the taxpayer is in a lower rate bracket. These provisions allow taxpayers to claim deductions for costs of earning income before the costs are incurred or to defer recognition of current income until a future year. Examples include provisions that allow immediate expensing or accelerated depreciation of certain capital investments and others that allow taxpayers to defer recognition of income on contributions to and income accrued within qualified pensions and retirement plans.

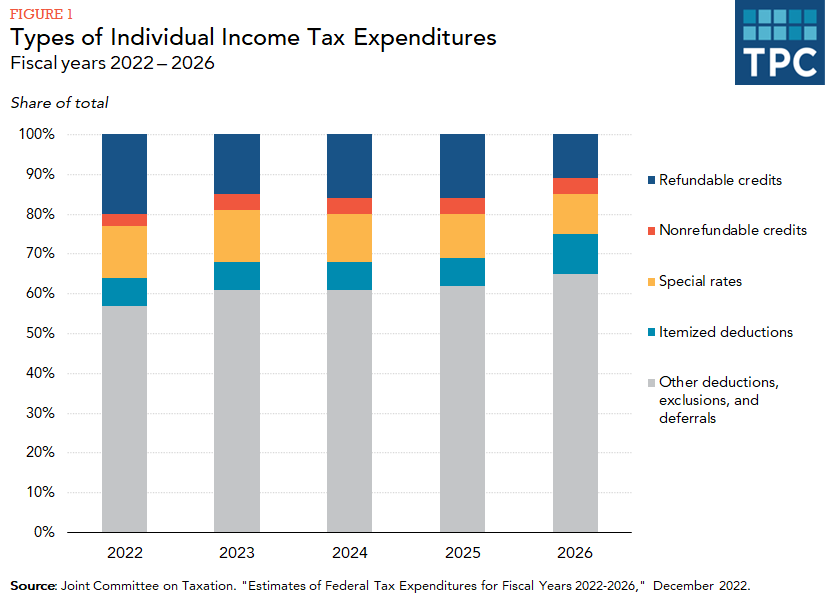

Exclusions, deductions, and deferrals of income recognition, excluding itemized deductions, will account for 61 percent of individual income tax expenditures in fiscal year 2024, refundable credits for 16 percent, special rates for 12 percent, itemized deductions for 7 percent, and nonrefundable credits for 4 percent (figure 1).

Updated January 2024

Joint Committee on Taxation. 2022. “Estimates of Federal Tax Expenditures for Fiscal Years 2022–2026.” JCX-22-22. Washington, DC.

Calame, Sarah and Eric Toder. 2021. “Trends in Tax Expenditures: An Update.” Washington, DC: Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center

Sammartino, Frank and Eric Toder. 2020. “Tax Expenditure Basics.” Washington, DC: Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center.