What tax changes did the Affordable Care Act make?

The Affordable Care Act made several changes to the tax code intended to increase health insurance coverage, reduce health care costs, and finance health care reform.

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) made several changes to the tax code intended to increase health insurance coverage, reduce health care costs, and finance health care reform.

To increase health insurance coverage, the ACA provided individuals and small employers with a tax credit to purchase insurance and imposed taxes on individuals with inadequate coverage and on employers who do not offer adequate coverage. To reduce health care costs and raise revenue for insurance expansion, the ACA imposed an excise tax on high-cost health plans. To raise additional revenue for reform, the ACA imposed excise taxes on health insurers, pharmaceutical companies, and manufacturers of medical devices; raised taxes on high-income families; and increased limits on the income tax deduction for medical expenses.

ACA tax provisions in effect in 2023 include the following:

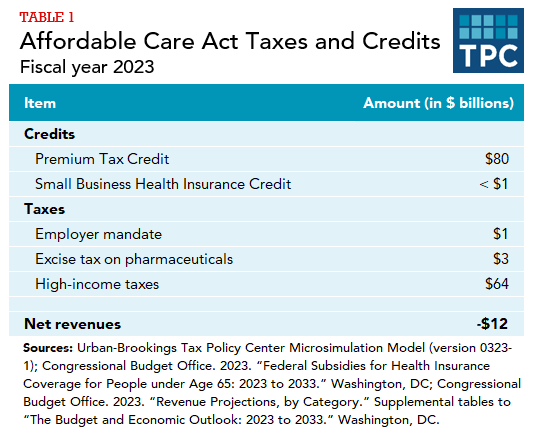

A refundable tax credit for families to purchase health insurance through state and federal marketplaces. Tax filers must have incomes greater than the federal poverty level (FPL), be ineligible for health coverage from other sources, and be legal residents of the United States. The Premium Tax Credit (PTC) is projected to cost $80 billion in fiscal year 2023. After 2025, enhancements made by American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 and extended by the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 will expire and the PTC will be less generous and only be available to families with incomes below 400 percent of FPL.

A tax credit for small employers to purchase health insurance for their workers. Employers must have fewer than 25 workers whose average wages are less than $50,000. Employers can only receive the credit for up to two years. The small-employer health insurance credit is projected to cost less than $1 billion in 2023.

A tax on employers offering inadequate health insurance coverage (the “employer mandate”). The tax applies to employers with 50 or more full-time equivalent employees. Employer mandate receipts are projected to be $1 billion in fiscal year 2023.

An excise tax on pharmaceuticals. The tax applies to manufacturers and importers of prescription drugs with sales of over $5 million. Excise tax receipts are projected to be $3 billion in 2023.

An additional 0.9 percent Medicare tax on earnings and a 3.8 percent tax on net investment income (NII) for individuals with incomes exceeding $200,000 and couples with incomes exceeding $250,000. The additional Medicare tax is projected to raise $17 billion and the NII tax is projected to raise $46 billion in 2023. Nearly all families affected by the additional Medicare tax and NII tax are in the top 5 percent of income, with most of the burden borne by families in the top 1 percent of income.

A number of ACA taxes have been repealed since passage of the ACA. Repealed provisions include:

A tax on individuals without adequate health insurance coverage (the “individual mandate”). Many individuals were exempt from the tax, including those with incomes low enough that they are not required to file a tax return, those whose premiums would exceed a specified percentage of income, and unauthorized immigrants. The 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act eliminated the individual mandate starting in 2019. Individual mandate receipts were $4 billion in 2018.

An excise tax on employer-sponsored health benefits whose value exceeds specified thresholds (the “Cadillac tax”). Including the impact on income and payroll taxes, the tax on high-cost health plans was projected to raise $8 billion in 2022 with the revenue gain growing rapidly over time, reaching $39 billion by 2028. The Cadillac tax would have reduced after-tax incomes the most in percentage terms for middle-income families. However, the Cadillac tax was repealed by the Further Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2020.

Excise taxes on health insurance providers and medical device manufacturers and importers. After enactment Congress often suspended both taxes and then legislation passed in late 2019 permanently repealed the medical device tax starting in 2020 and the health-insurer tax starting in 2021. The excise tax on health insurance providers raised $15 billion in 2020 the tax on medical devices raised $2 billion in 2015.

An additional limit on the medical expense deduction. Pre-ACA, taxpayers could deduct medical expenses exceeding 7.5 percent of income when calculating taxable income. The ACA increased the threshold to 10 percent of income, but then later legislation temporarily lowered the limit back to 7.5 percent before the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021 permanently set the threshold at the lower Pre-ACA level. The additional limit on the medical expense deduction would have increased revenues by about $2 billion in 2023.

Tax changes were an important component of the package of reforms enacted by the ACA. Any major change to the ACA would require making tax policy decisions with implications for health insurance coverage, the budget deficit, and the distribution of after-tax income.

Updated January 2024

Congressional Budget Office. 2023. “Federal Subsidies for Health Insurance Coverage for People under Age 65: 2023 to 2033.” Washington, DC: Congressional Budget Office.

Congressional Budget Office. 2023. “Revenue Projections, by Category.” Supplemental tables to The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2023to 2033. Washington, DC: Congressional Budget Office.

Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center. “Microsimulation Model, version 0323-1”

Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center. 2020. “T20-0256 – Repeal 0.9 Percent Additional Medicare Tax Enacted by the Affordable Care Act (ACA), Updated Analysis by ECI Percentile, 2022”; “T22-0238 - Tax Benefit of the Net Investment Income Tax, Baseline: Current Law, Distribution of Federal Tax Change by Expanded Cash Income Percentile, 2022”; T18-0217. “Repeal Cadillac Tax, Premiums Revert to Pre-Cadillac Tax Levels, Baseline: Current Law, Distribution of Federal Tax Change by Expanded Cash Income Percentile, 2028”. Washington, DC.