The voices of Tax Policy Center's researchers and staff

President Trump’s proposed 2018 budget would result in deep cuts to federal payments to states. Federal funds currently account for nearly a third of state expenditures, so if enacted, Trump’s budget would kick huge decisions to statehouses: raise taxes, reduce benefits, or eliminate services.

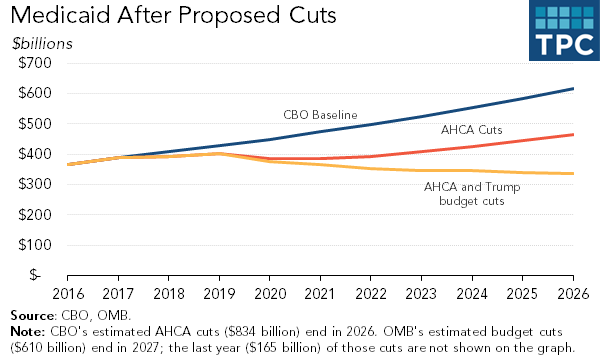

Start with state government’s largest expenditure, Medicaid (nearly 30 percent). The Trump budget, combined with proposals in the House-passed American Health Care Act (AHCA), could cut the federal contribution to Medicaid more than $1 trillion over the next decade.

The AHCA would gradually eliminate the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion and change the federal match rate to a per-capita cap, which would grow at a slower rate than current Medicaid spending. In total, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates the AHCA changes would reduce federal Medicaid spending $834 billion over 10 years. The president’s budget includes another $600 billion in cuts, which appear to be in addition to the AHCA’s cuts. However, in line with the rest of this “black box” budget, even the White House doesn’t know for sure (or won’t say). But if they are combined, they would cut federal Medicaid funding nearly in half by 2026.

In its typical understated way, the CBO describes what comes next. Its March score of the AHCA (which looked a lot like the new CBO score), said, “How individual states would ultimately respond [to Medicaid cuts] is highly uncertain.”

That’s because Trump and the House Republicans are offering states a trade-off that would fundamentally change the way the half-century old program works. Under the current funding mechanism, the federal government pays a percentage of program costs no matter how fast they grow. The Trump-House GOP replacement would cap federal contributions based on each state’s number of enrollees (per-capita cap), or offer funds in a block grant. States would get far more control over how they run the program—but with far less money to do so.

So would states raise taxes to fill the funding gap or drop people from health care? Connecticut and New Jersey established task forces to prepare responses to Medicaid cuts. But Texas Gov. Gregg Abbot cheered Obamacare’s “spiraling to a hasty death.” Regardless, even states that want to maintain current coverage levels would need billions in new dollars every year. That’s a huge lift for states and why CBO estimated 14 million would lose Medicaid if AHCA became law.

Then there’s the rest of Trump’s budget. Along with some budget tricks, the administration finds balance by reducing non-defense discretionary spending 2 percent each year—totaling $1.4 trillion over 10 years.

Specifically, it proposes double-digit percentage cuts to the departments of Agriculture, Commerce, Education, Health and Human Services, Housing and Urban Development, and Transportation, all of which send money to states. Some examples of program cuts over the 10-year period:

- $200 billion cut from the SNAP (i.e., food stamps); currently completely federally funded, the budget also proposes requiring states to chip in a quarter of funds.

- $100 billion cut from the Highway Trust Fund, which sends money to states for highway and mass transit projects.

- $20 billion from Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, a joint federal-state funded program that provides welfare cash.

The National Association of State Budget Officers has a good roundup of the numerous other state administered programs cut or eliminated in the budget, including EPA grants, community development block grants, rental assistance programs, low income home energy assistance programs, and more. And what about the administration’s new social program, paid parental leave? The budget forces states to raise their unemployment taxes to pay for it.

Would states raise taxes to keep these programs? Does the equation change if the state and local tax deduction is repealed?

There are a lot of unknowns, but we know the administration and Congress are both interested in cutting federal payments to states, and that states don’t have enough money to replace those funds. As with health care, the federal budget cuts would probably reduce services and beneficiaries. But because they’re state programs, what each state does is highly uncertain.

Posts and comments are solely the opinion of the author and not that of the Tax Policy Center, Urban Institute, or Brookings Institution.

Andrew Harnik/AP Photo