The voices of Tax Policy Center's researchers and staff

What if, when you filed your income tax return, you were asked if you’d like to register to vote or update your voter registration? To find out, I conducted an experiment to test of this simple idea, and the results were powerful: We doubled the voter registration rate, and our effects were even larger for younger people.

There are plenty of reasons to be optimistic about what I’ve referred to as “Filer Voter” (like Motor Voter but for taxes!).

- More than 150 million households file their taxes every year.

- Compared to our arduous federal income tax system, voter registration requires very little additional paperwork. Unlike the income tax form, the voter registration form actually fits on a postcard.

- And there is a lot of research, including some of my own work, suggesting that Americans see taxpaying, like voting, as part of being a good citizen.

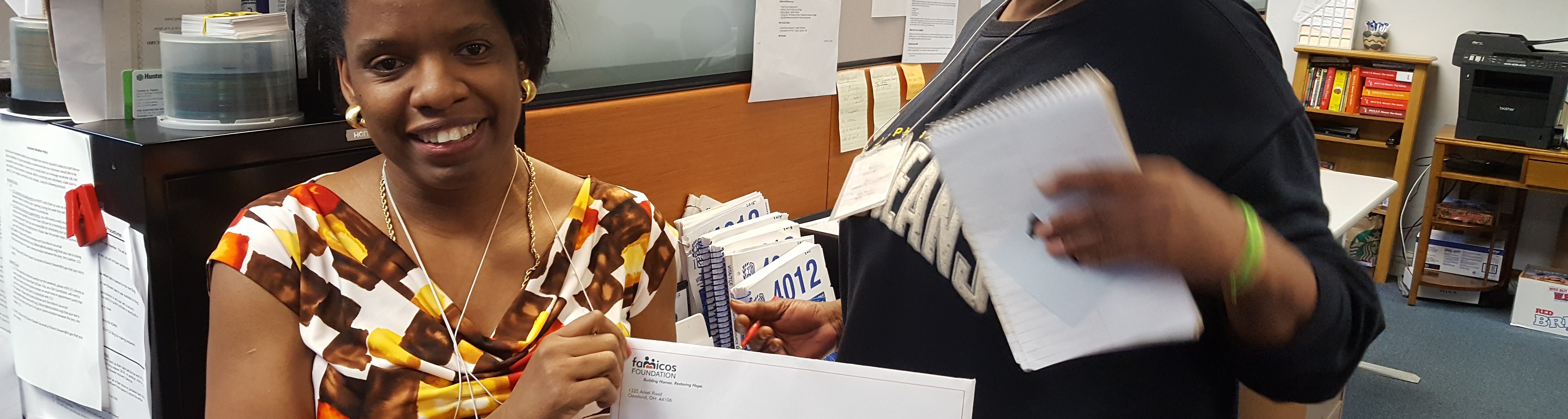

It all sounds good. But a lot of things sound good in principle. To see if the idea works, we conducted a large-scale field experiment, working with more than 4,500 filers at seven nonprofit free tax preparation “Volunteer Income Tax Assistance” (VITA) sites in Dallas, Texas and Cleveland, Ohio. I described the results in a new paper and at an event this week hosted by the Brookings Institution and the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center.

Extrapolating from the results, if you implemented a voter registration project at every VITA site in America, you could register 115,000 people, including 63,000 who would not otherwise register to vote. If you could expand the program to all 150 million-plus tax filing households, the impact would be even larger.

Ok, so Filer Voter got tax filers registered. But did they actually vote? We looked in Ohio, where the primary election was late enough that the tax filers we registered were eligible to vote. In Ohio’s primary election, turnout for those who participated in Filer Voter was slightly higher than the state average.

The turnout results are notable because VITA sites serve low- and moderate-income Americans, who tend to be drastically underrepresented at the polls. In 2016, only 52 percent of individuals making less than $50,000 voted, compared to 74 percent of those making more. At our sites, the average participant’s income was just over $23,000 a year in Cleveland and around $27,000 in Dallas. Overall, our participants voted at the same rate as other voters.

We also found that voter registration did not measurably slow tax preparation services. In the experiment, we added voter registration to the VITA site’s welcome and intake process, before filers met with tax preparers. We thought it would be better to add the additional service at the beginning when other materials were being filled in, so people could leave right after having their tax returns prepared and filed. As a result, this additional service could have a positive effect on voter registration with little or no additional work by tax preparers.

Filer Voter is not a silver bullet, no single policy could be. But based on these results, it could be a meaningful way to increase political participation. Besides, this country was founded on the idea of “no taxation without representation.”

Posts and comments are solely the opinion of the author and not that of the Tax Policy Center, Urban Institute, or Brookings Institution.