The voices of Tax Policy Center's researchers and staff

Some low- and middle-income families in Colorado, Minnesota, New Mexico, and North Dakota are facing state income tax hikes. And the larger the family, generally the bigger the tax increase.

Who designed this anti-family tax? No one, really. Instead, it’s the result of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), the complex relationships between federal and state tax law, and the inability of some states to respond to the new federal law. However, a new Tax Policy Center paper shows there is a relatively simple solution to the problem: States should create their own refundable child tax credit (CTC). Even states whose residents don’t face a tax hike could improve their tax systems for low- and middle-income families by building on the federal changes and adopting a refundable CTC.

First, how we got here. Overall, the TCJA reduced federal income taxes for many low- and middle-income families through a push and pull of tax changes: increasing the standard deduction and expanding the CTC, but eliminating the personal exemption. Notably, these changes flowed through to state tax laws in states that piggybacked off those federal rules.

When Congress passed the TCJA, eight states—Colorado, Idaho, Minnesota, New Mexico, North Dakota, South Carolina, Utah, and Vermont—replicated both the federal standard deduction and the personal exemption in their own state income taxes (so did the District of Columbia but its situation is more complicated). Maine used only the federal personal exemption but not the standard deduction in its state income tax. None of these states had a state-level CTC that automatically mirrored the increased federal CTC.

This created the problem. If a state eliminates its personal exemption but does not replace it with a CTC or some other offsetting tax change, families with several children could pay more in state income tax than they would have under the old law.

How states responded (or didn’t) to the federal legislation

Colorado accepted the new federal laws and made no offsetting changes to its own laws. This is how the changes affect low- and middle-income households:

As the chart shows, Colorado income taxes go up with each additional child because every lost personal exemption increases the family’s taxable income—and, thus, its tax. The story is similar in Minnesota, New Mexico, and North Dakota because they also did not pass legislation in response to the new federal tax law.

Some states did respond to the federal legislation and modify their income tax laws. Idaho and Maine both followed the federal government’s lead and created a state CTC (among other changes). We estimate that both states prevented tax increases on low- and middle-income families, and they cut taxes for some filers, especially those with higher incomes.

Meanwhile, Vermont decided to fix the problem by creating a state-defined personal exemption and increasing its refundable earned income tax (EITC) credit from 32 percent to 36 percent of the federal credit (among other changes). These actions not only prevented state income tax hikes but, because the EITC is refundable, delivered state income tax cuts to low-income families.

A better option: refundable child tax credit

Each state got something right, but could have done better by combining the two approaches. Adding a state CTC keeps the state tax laws in line with the federal tax code, which is simpler for filers and administrators. But a nonrefundable CTC, while eliminating a tax hike, won’t help many families. For example, a single parent in Idaho who earns $60,000 and has two children will get a state income tax cut of roughly $300 thanks to that state’s adjustments post-TCJA. But the same family earning just $20,000 will get no state income tax cut at all. By contrast, the same family earning $20,000 but living in Vermont gets a $200 state income tax cut because the state expanded its refundable EITC.

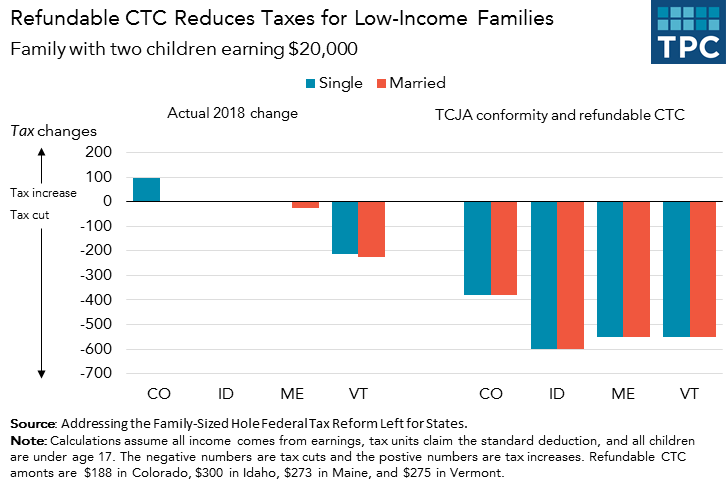

That’s why adding a refundable CTC can be a great idea for states with an income tax. To show why, we modeled the actual responses of Colorado, Idaho, Maine, and Vermont to the TCJA, then looked at what would happen if each state had only adopted the TCJA changes in their state income tax and added a refundable CTC equal in value to the former personal exemption (see the paper for calculations). The chart below shows what would happen to families with two children earning $20,000, a household that generally would not benefit from a nonrefundable credit.

With the refundable CTC, families in all four states would get a tax cut. Further, the CTC is flexible: States can make it more or less generous by changing the federal phase-in formula or limit revenue losses by changing the phase-out formula.

In contrast, states cannot make personal exemptions refundable. And keeping a personal exemption in your state tax code when the federal exemption is gone can create unnecessary confusion. This is why we recommend all 23 states with a personal exemption in their state income tax exchange it for a CTC. (We calculate equal value CTCs for each of these states in the paper.)

Adopting a state-level refundable CTC is a smart solution to a tricky problem for the four states where families are facing possible tax increases next year, and a good idea for any state policymaker looking for ways to assist low- and middle-income families with children.

Posts and comments are solely the opinion of the author and not that of the Tax Policy Center, Urban Institute, or Brookings Institution.

Share this page

Joseph Sohm/Shutterstock