The voices of Tax Policy Center's researchers and staff

Politicians love sales tax holidays as good campaign fodder. Retailers celebrate them with gaudy signs announcing tax-free shopping, and consumers line up to take advantage of the deals. But economists and policy analysts across the ideological spectrum condemn them as poorly targeted tax policy that produces little economic benefit. Is there any fiscal justification for all this feel-good shopping?

More than a third of states that levy a general sales tax (17 out of 45) will stage sales tax holidays this year, most of them in late summer when clothing and school supplies are briefly exempt from the sales tax before school starts. New York held the first sales tax holiday in 1997 to encourage residents to purchase clothing in-state instead of across the Hudson in New Jersey where clothing is never taxed. Other states, often those facing competition from neighboring states, soon joined suit: seven states had holidays in 2000, rising to 15 states plus the District of Columbia in 2006.

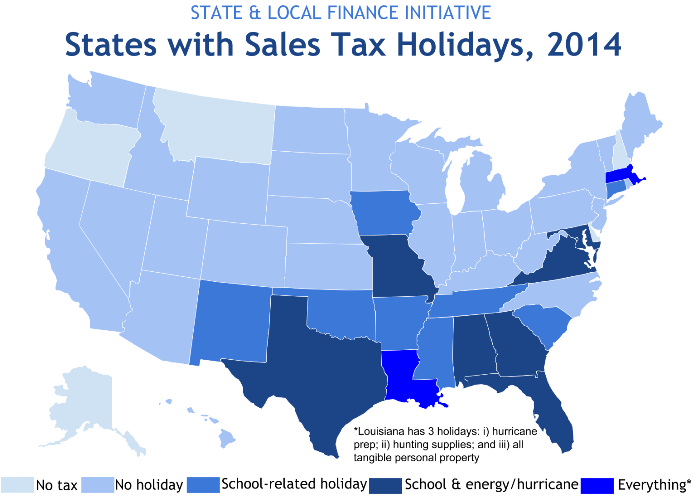

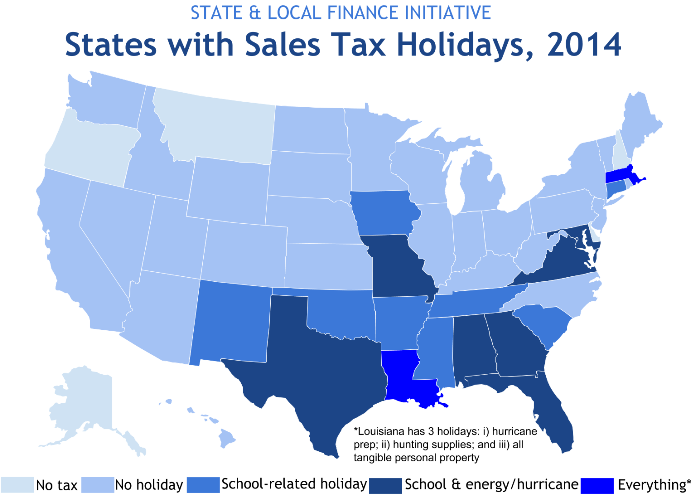

Since then holidays have been added (Arkansas, Mississippi, Oklahoma, and Tennessee), repealed (DC, New York, and North Carolina), and dropped but then brought back (Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, and Massachusetts), but the number of states with holidays has roughly stayed the same. States with sales tax holidays are mostly clustered in the South (12 of the 17 states), and are almost nonexistent in states west of Missouri (see map).

Every state offering a sales tax holiday this year ties one of its tax breaks to back-to-school shopping, exempting clothing, school supplies, and/or computers from the sales tax in July or August. Louisiana and Massachusetts go further and extend their late-summer tax exemptions to all tangible personal property. Eight states offer additional sales tax holidays to encourage other timely purchases (see map). Florida, Louisiana, and Virginia exempt hurricane-preparation equipment from the sales tax for a weekend in late May and Alabama has a similar holiday in February. Florida, Georgia, Maryland, Missouri, Texas, and Virginia have sales tax holidays (at various times) for energy-efficient products. And Louisiana stands alone with its sales tax holiday for firearms, ammunition, and hunting supplies.

Sales tax holidays don’t make sense as tax policy. While ostensibly a tax break to help working families afford the costs of sending kids back to school, the holidays are more beneficial to affluent shoppers, who have the means to change the timing and amount of their purchases. And because consumers are mostly shifting (rather than increasing) their purchases, the holidays do little (if anything) to boost economic growth.

But there are two reasons why sales tax holidays might not be all bad.

First, as policy-makers search for ways to make their states more competitive, a sales tax holiday might be the least-bad option. Sales tax holidays don’t cost much revenue because they last only a few days and the prices of eligible items are typically capped. For example, Maryland's FY 2013 tax holidays cost about $11 million, less than a third of a percent of the state’s $4.1 billion in sales tax revenue collected that year. Meanwhile, North Carolina recently eliminated its holiday but deeply cut its income and corporate taxes in a tax reform package. The sales tax holiday cost the state $14.5 million in 2011, a fraction of the half-billion-dollar price tag of the tax cuts this fiscal year. And if the economy goes south or adequate revenue does not materialize, holidays are far easier to change than other tax policies.

Second, shifting the timing of consumer’s purchases is sometimes worthwhile. That’s not likely the case for back-to-school holidays—families buy clothing throughout the year, not just in late summer—but encouraging residents to stock up on emergency supplies before hurricane season could help when storms hit.

In some situations, sales tax holidays can make sense. But generally, they’re bad tax policy unless the alternative is large tax cuts with dubious growth assumptions, and not just for a weekend but for the whole year.

Posts and comments are solely the opinion of the author and not that of the Tax Policy Center, Urban Institute, or Brookings Institution.