The voices of Tax Policy Center's researchers and staff

Two tax benefits—the child and dependent care tax credit (CDCTC) and the employer-provided child care exclusion—help families pay for work-related child care, but neither does much to assist low-income parents. During the 2016 election, Donald Trump proposed adding three new tax benefits for child care but a better fix would simply eliminate the exclusion. That would save about $1.1 billion a year, which Congress could use to provide child care benefits for families who make too little to take advantage of the current benefits.

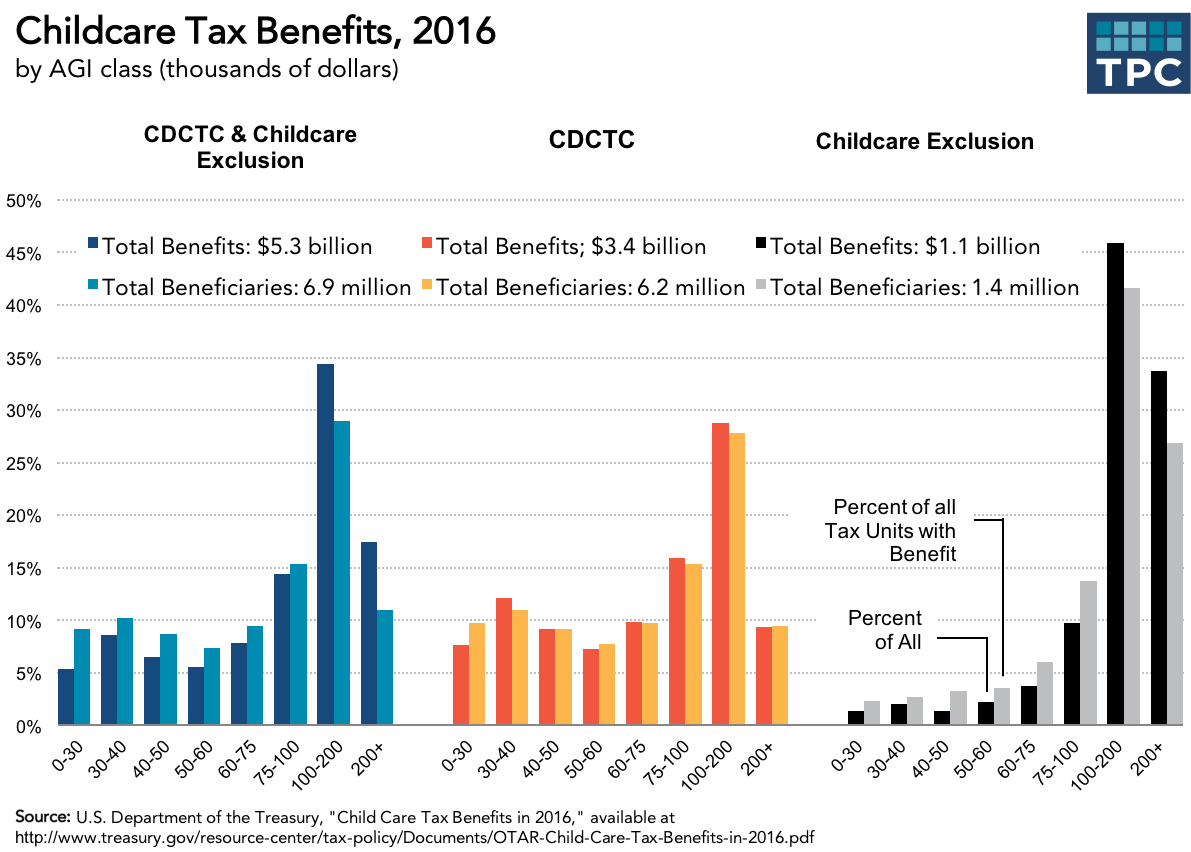

The three new child care tax benefits proposed by the president include an expanded credit for low-income families, a deduction for higher income families, and a child care savings account. The Tax Policy Center estimates that the proposal would cost about $11 billion a year, roughly twice the $5.3 billion annual cost of current benefits. The new benefits would make it harder for parents to figure out their best options and would disproportionately benefit high-income families: 70 percent of the tax savings would go to families with income of $100,000 or more.

The existing benefits are complicated, as I have explained elsewhere. If your employer offers the child care exclusion (less than one-third of all workers have access to this benefit), you can set aside up to $5,000 each year to pay child care expenses and not have to pay either payroll or income taxes on that money. You can also claim a CDCTC equal to a percentage of child care expenses up to $3,000 per child (and $6,000 per family). The credit rate declines from 35 percent for families with income under $15,000 to 20 percent for those with income of $43,000 or more. Families can benefit from both provisions if they spend more on child care than they set aside under the exclusion and qualify for larger credit expenses than they set aside. Consider, for example, a family with two children that pays $6,000 for child care throughout the year. If they set aside $5,000 in the exclusion, they can claim a credit on the remaining $1,000 of expenses. That’s pretty complicated.

On top of that, many low-income families receive no benefit from either the CDCTC or the exclusion. The credit can only offset income taxes—in tax-speak, it’s not “refundable.” As a result, low-income families that have too little income to owe federal income tax cannot use the credit. For example, in 2016, a married couple with two children and income under $28,800 owes no federal income tax and thus can’t claim the credit. Almost 40 percent of CDCTC benefits that year went to families with Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) of $100,000 or more compared with just 5 percent for families with income under $30,000 AGI (figure).

Benefits from the exclusion are distributed even more unevenly–80 percent of the tax savings in 2016 went to families with income of $100,000 or more. In large part, that’s because the value of the exclusion rises with the family’s tax rate but it’s also because higher-income workers are more likely to have access to such plans. The highest average benefits go to those in the highest income groups.

If the exclusion were eliminated, most families who currently benefit from it would turn to the CDCTC instead. Because the credit is limited to 20 percent of allowable expenses—and that percentage is higher for lower-income families—the distribution of benefits would be more uniform. Very low-income families who don’t owe taxes would still be left out, but making the CDCTC refundable would solve that problem. Congress could also expand existing refundable credits such as the earned income tax credit (EITC) or child tax credit (CTC) that already benefit low-income families, possibly focusing additional benefits on families with young children that most likely to need child care in order to work.

Child care is an important issue facing many families, particularly those with young children. Congress should consider simplifying and expanding current benefits rather than further complicating the problem by creating three new benefits.

Posts and comments are solely the opinion of the author and not that of the Tax Policy Center, Urban Institute, or Brookings Institution.

Topics

Share this page

In this May 6, 2015, file photo Saryah Mitchell, sits with her mother, Teisa, Gay, left, a rally calling for increased child care subsidies at the Capitol in Sacramento, Calif. In much of the U.S., families spend more on child care for two kids than on housing. And if you’re a woman, it’s likely you earn less than your male colleagues even though one in four households with kids relies on mom as the sole or primary breadwinner. (AP Photo/Rich Pedroncelli, File)