The voices of Tax Policy Center's researchers and staff

Here is one way to think about the Congressional Budget Office and Joint Committee on Taxation score of the House Republican health bill: By cutting Medicaid by $880 billion and reducing insurance subsidies by $680 billion, the American Health Care Act (AHCA) would fund $883 billion in tax cuts over the next decade-- mostly for high-income households-- as well as some additional health-related spending. And it would reduce the projected federal debt by $337 billion through 2026.

The CBO’s 10-year projection of Medicaid cuts underestimates the real effects since the reductions would not kick in until 2020 and the cap on federal contributions would gradually but inexorably reduce federal payments to the program. For example, while the cost savings over the first 10 years is $880 billion, nearly one-fifth of that-- $155 billion--would occur in 2026 alone.

The CBO/JCT score provides a window into how much less generous the GOP refundable tax credits would be than the ACA’s subsidies. The congressional scorekeepers project the 10-year cost of the House GOP premium subsidies and its grants to states to help stabilize insurance markets would be $441 billion. That’s about two-thirds the $679 billion value of the ACA’s subsidies, including support for individuals buying on the health exchange and tax credits for small employers. The lower cost is a result of two effects: Less generous subsidies and fewer people taking advantage of them because they do not buy insurance (in part because they could not afford it without the subsidies).

The Tax Policy Center has estimated that the highest-income one percent of households would get 40 percent of the benefits of repealing the ACA’s tax increases. While middle-income households would get an average tax cut of about $300, or 0.5 percent of their after-tax income; the top 1 percent would get an average tax cut of $37,000, or 2.1 percent of their after-tax income.

Along with our colleagues at the Urban Institute, TPC will soon project the distributional and coverage effects of the AHCA’s premium subsidies and its repeal of the ACA’s subsidies and penalties. However, we have some general idea of what would happen.

The AHCA would adjust subsidies by age (younger people would get $2,000, older buyers who get $4,000) with a phase out for those making more than $75,000 ($150,000 for couples). However, the plan would also allow insurance companies to raise premiums substantially for those in their 50s and 60s. The current law ACA provides greater assistance to those with less income, and phases out its assistance at about $47,000 for singles and $64,000 for childless couples. It caps insurance premiums for older buyers at no more than three times premiums for younger consumers. By contrast, AHCA would allow insurers to charge older buyers up to five times as much.

CBO projects that these tax changes and cuts in federal Medicaid payments would reduce the number of Americans with health insurance by 14 million in 2018, 21 million in 2020—when the Medicaid cuts begin to take effect—and 24 million by 2026. The measure would nearly double the number of uninsured.

While many details of the AHCA have yet to be sorted out, it appears that the bill would fund tax cuts, mostly for high-income people, by reducing government assistance—either though insurance subsidies or Medicaid—for low- and moderate-income households.

Posts and comments are solely the opinion of the author and not that of the Tax Policy Center, Urban Institute, or Brookings Institution.

Topics

Share this page

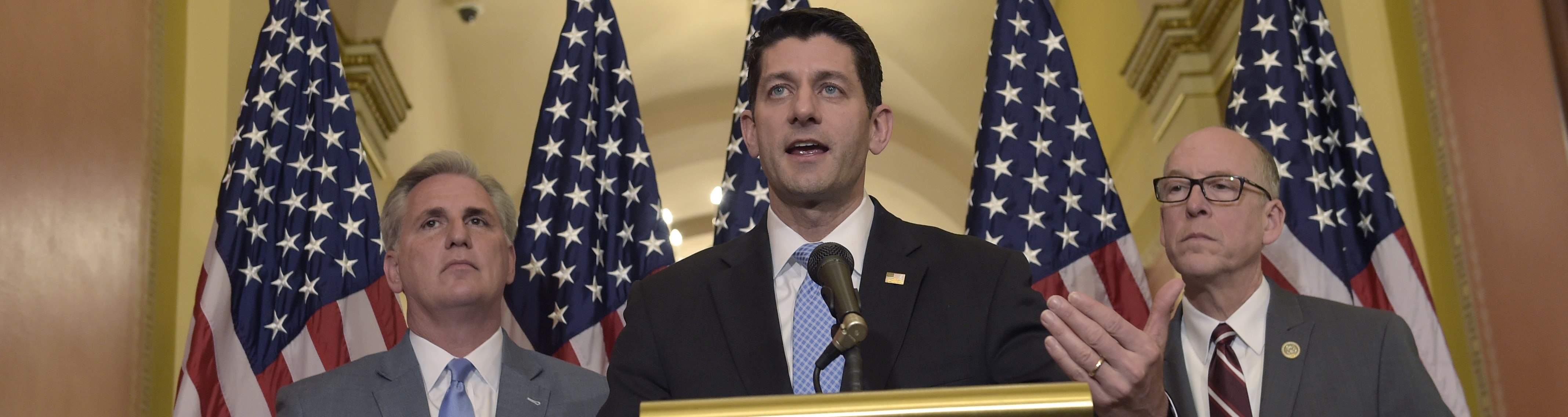

House Speaker Paul Ryan of Wis., center, standing with Energy and Commerce Committee Chairman Greg Walden, R-Ore., right, and House Majority Whip Kevin McCarthy, R-Calif., left, speaks during a news conference on the American Health Care Act on Capitol Hill in Washington, Tuesday, March 7, 2017. (AP Photo/Susan Walsh)