The voices of Tax Policy Center's researchers and staff

More than three years after the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the shift to remote work for many office workers has put the future of commercial real estate, and potentially city government budgets, on shaky ground.

One data and analytics group estimated that commercial property values are down 12 percent over the past 12 months, putting today’s values on par with those in May 2018. In comparison, residential home values are about 50 percent higher than in mid-2018.

The divergence in commercial and residential property values makes it hard to predict the fiscal consequences for local governments broadly. Total property tax revenue accounts for 30 percent of local general revenue, but the pain from this transition will likely be concentrated in major cities with big commercial districts.

For example, the decline in office values is projected to cost the District of Columbia $464 million in combined tax revenue over the next three fiscal years. Similarly, San Francisco could lose $150 million to $200 million annually by 2028, about 5-6 percent of all current property taxes. In Boston, almost three quarters of its current total general revenues comes from property taxes; of that, more than half comes from commercial, industrial and tangible personal property (22 percent comes from office buildings alone).

Changes in workers’ expectations about the location of work and declines in urban population suggest these recent trends could be here to stay. A recent academic study estimated that New York City could see a long-run decline of 44 percent in the value of office buildings, which equates to about $50 billion. This has prompted worries beyond the office real estate market. Overall, the authors approximate a destruction of over $500 billion in office value in the US.

Property tax data challenges

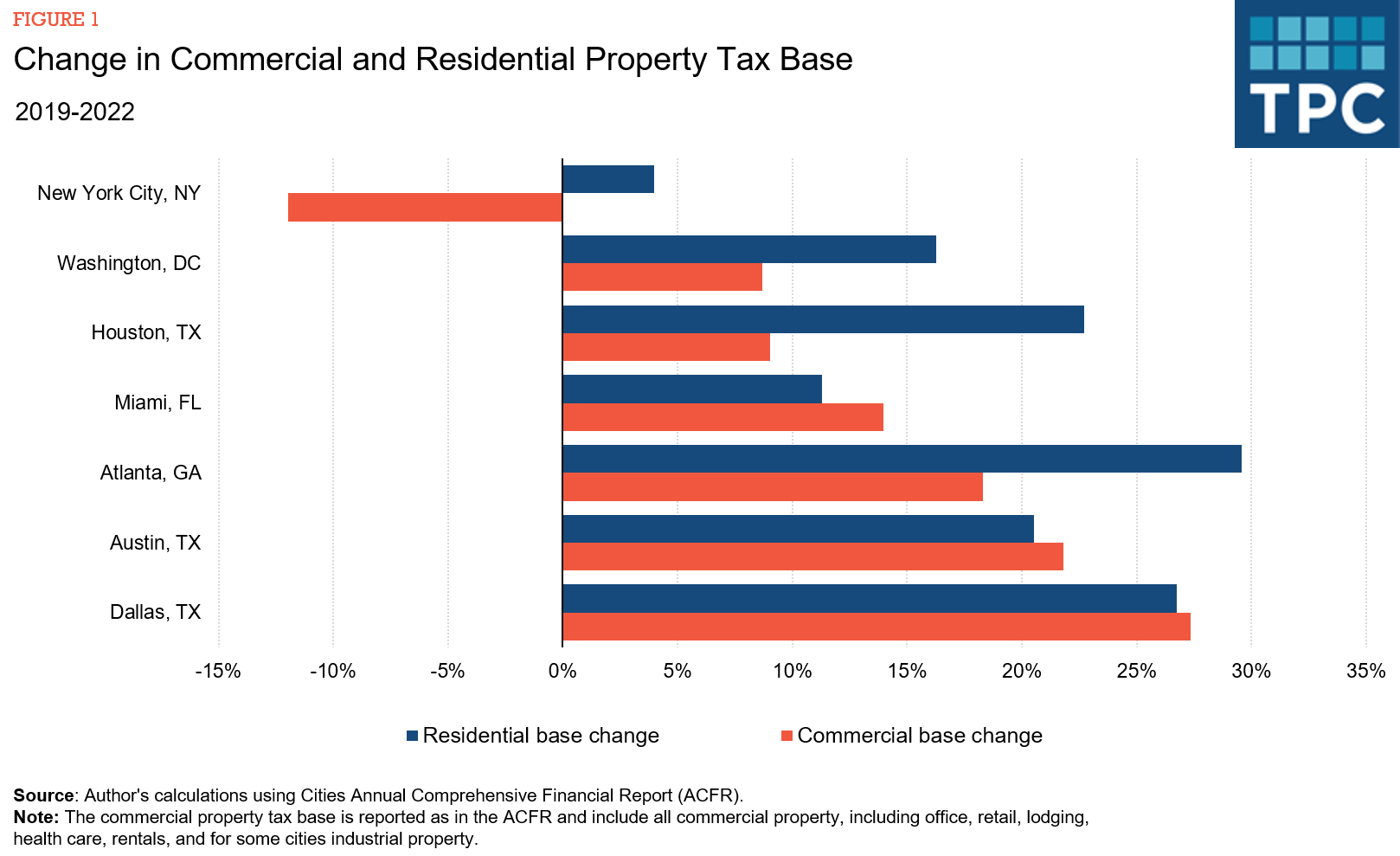

Based on data from some large US cities, the property tax base of both commercial and residential real estate grew between 2019 and 2022, with the notable exception of New York. In Austin, Dallas, and Miami, the tax base for commercial real property actually grew faster than residential property.

However, commercial valuations can be a lagging indicator. Many leases are long-term contracts, so some leases signed before 2020 will be renegotiated over the next decade; a drop in demand for office space could further lower their value.

Although more workers have returned to the office, recent data suggests office occupancies hover between 40 and 60 percent in the largest cities. And local governments assess values on different schedules. Many governments have not yet accounted for recent changes in commercial property values in their tax data.

Cities also use different assessment methods that can limit the decline in tax collections from declining property values. New York, for example, uses net operating income submitted by owners of commercial buildings, rather than recent sales, to determine assessed value, and phases in those changes over five years. The city comptroller estimated that a “doomsday” scenario where office values decline by 40 percent between 2023 and 2029 would lead to a decline in property tax levies of 3 percent in 2027.

All of this could make it harder for cities to map out their fiscal futures.

Which cities are most likely to suffer from declining office values?

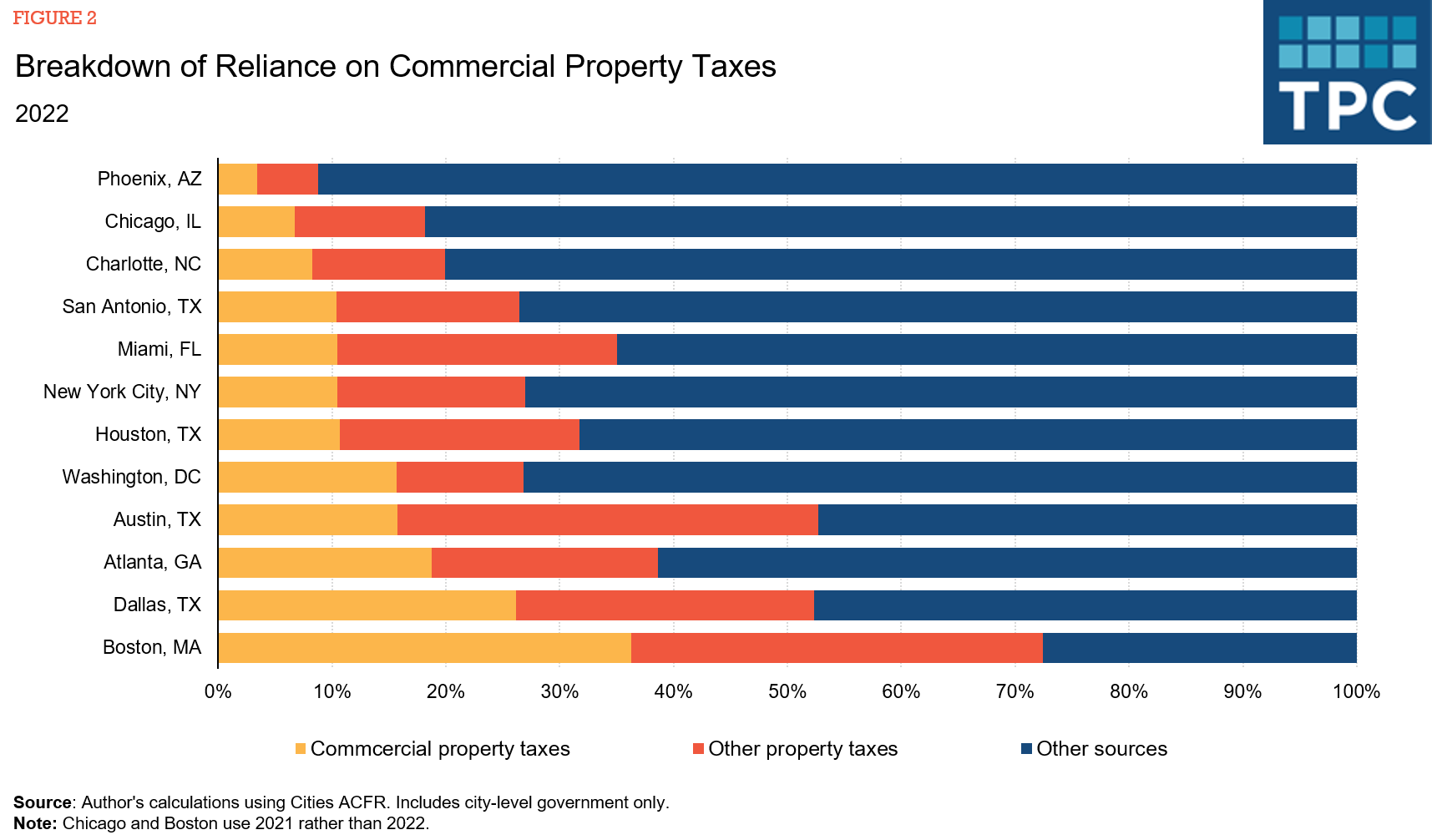

Of the 12 major cities I analyzed, Boston has the highest reliance on commercial property taxes. Taxes on commercial property account for almost 36 percent of its total general revenues. Dallas (26 percent) and Atlanta (19 percent) also have high reliance on commercial property taxes. In contract, commercial property taxes are less than 10 percent of general revenue in Phoenix (3 percent), Chicago (7 percent), and Charlotte (8 percent).

This analysis focuses on city-level government only, but school districts and county governments also rely heavily on property taxes, and could be even more impacted by a decline in commercial property values.

How will local governments react?

Unlike the federal government, cities face strict budget constraints and can usually only borrow to fund long-term capital investments, such as infrastructure. City governments will have three traditional choices.

One, they could increase the tax rate on commercial properties. This might raise revenue, but it could also increase the tax burden of commercial tenants and put further downward pressure on demand, exacerbating the core problem.

Two, they could curtail spending and services. This might help cities balance budgets, but it could potentially harm the city’s most vulnerable residents and make it a less attractive place to live and do business.

Third, they could make up for the shortfall by increasing tax revenues from other sources, such as residential property, sales taxes, or fines and fees. However, this could make these local tax systems more regressive.

Cities may get creative and try something new. But to do that, they must start planning now. We don’t have perfect data, but we know office values are falling, so major cities must find ways to become less reliant on commercial property taxes.

Posts and comments are solely the opinion of the author and not that of the Tax Policy Center, Urban Institute, or Brookings Institution.

Share this page

Photo via Pexels/Polinna Zimmerman