The voices of Tax Policy Center's researchers and staff

The revised version of Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell’s health bill would retain the Affordable Care Act’s 3.8 percent Net Investment Income Tax and its 0.9 percent Medicare surtax, both of which are imposed on individuals making $200,000 or more and couples making $250,000. Retaining those two provisions would make the plan’s tax cuts less regressive than McConnell’s original plan, according to a new analysis by the Tax Policy Center.

TPC looked only at the plan’s proposed changes to the ACA taxes. Its analysis includes proposals to repeal the ACA’s excise taxes on individuals without insurance and firms that do not offer adequate coverage to employees, and its more generous version of the medical expense deduction.

It did not analyze the effects of proposals to expand Health Savings Accounts or Flexible Savings Accounts. Nor did the analysis include changes to Medicaid or premium subsidies for those buying health insurance on the individual market. Those provisions are essentially the same in both bills.

A July 11 analysis by TPC and the Urban Institute’s Health Policy Center found those provisions of the initial McConnell plan would raise taxes and reduce government transfers for low-income households and increase net benefits for those with high incomes.

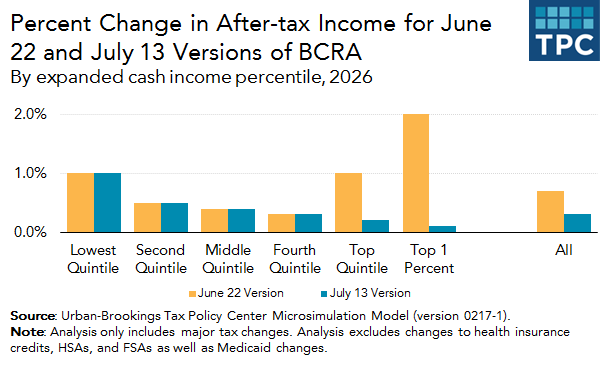

Because McConnell 2.0 would retain two taxes aimed at high-income households, it is not surprising that the proposal’s remaining tax cuts are less likely to benefit that group. Overall, the latest plan would cut average taxes by about $300 in 2026, compared to $670 in the initial version. And it would be less regressive.

Upper-income households would get the biggest dollar amount of tax cuts. However, the lowest income households get the largest average tax cuts as a share of their after-tax income while those with the highest incomes would get the smallest. TPC looked at tax changes for 2026, the year most provisions are fully effective.

For example, those households making about $28,000 or less would get an average tax cut of about $180 or 1 percent of their after-tax income. Middle-income households, who make between $54,000 and $93,000, would get an average tax cut of about $280 or 0.4 percent of their after-tax income, and those in the top 1 percent would get a tax cut of $2,900, which would equal 0.1 percent of their after-tax income.

That is significantly different from the first version of the Senate leadership plan, called the Better Care Reconciliation Act (BCRA). That bill would have given the biggest tax cuts, both in dollars and in share of after-tax income, to the highest income households and the smallest tax cuts to middle-income households. Thus, it would have been quite regressive.

The fate of a health bill is likely to be decided by changes in Medicaid and in individual insurance coverage—provisions that disproportionately affect low- and moderate-income households. But by retaining two taxes on upper-income households, the Senate leadership has made one portion of its plan much less regressive than it was.

Posts and comments are solely the opinion of the author and not that of the Tax Policy Center, Urban Institute, or Brookings Institution.

Topics

Share this page

J. Scott Applewhite/AP Photo