The voices of Tax Policy Center's researchers and staff

President Trump wants to do something about infrastructure. As a presidential candidate, he decried the state of American roads, bridges, transit, and airports, comparing the US to “a third world country,” and said his developer experience uniquely qualified him to fix it. He restated his commitment to infrastructure in his election night victory speech, first joint address to Congress, a statement of principles in his proposed FY2018 budget, an executive order, and in various meetings and press conferences.

But the tax bill working its way through Congress represents a missed opportunity for infrastructure. Trump, as well as Democratic and Republican members of Congress and President Obama, had floated a one-time “transition tax” on accumulated foreign earnings to shore up the Highway Trust Fund and finance new investments. But the current bills use those one-time revenues (estimated at $298 billion in the Senate bill and $293 billion in the House version) to pay for corporate tax rate reduction and other tax changes instead.

The House-passed bill also would eliminate tax-exempt private activity bonds (PABs) issued by state and local governments on behalf of private investors who participate in projects such as airports, hospitals, toll roads, and multi-family housing. And it would repeal the tax exemption for so-called advance refunding bonds used to refinance outstanding state and local government bonds when interest rates decline.

So, what happened to the president’s bold infrastructure agenda? Like many of his predecessors, he is running up against some hard truths.

First, there is little agreement on what needs to be done. Although most observers think the country needs to spend more on infrastructure, the consensus breaks down quickly from there. Should new revenues go to transportation or water? Highways or rail? Urban or rural highways? What about school buildings and court houses? Broadband and smart grids?

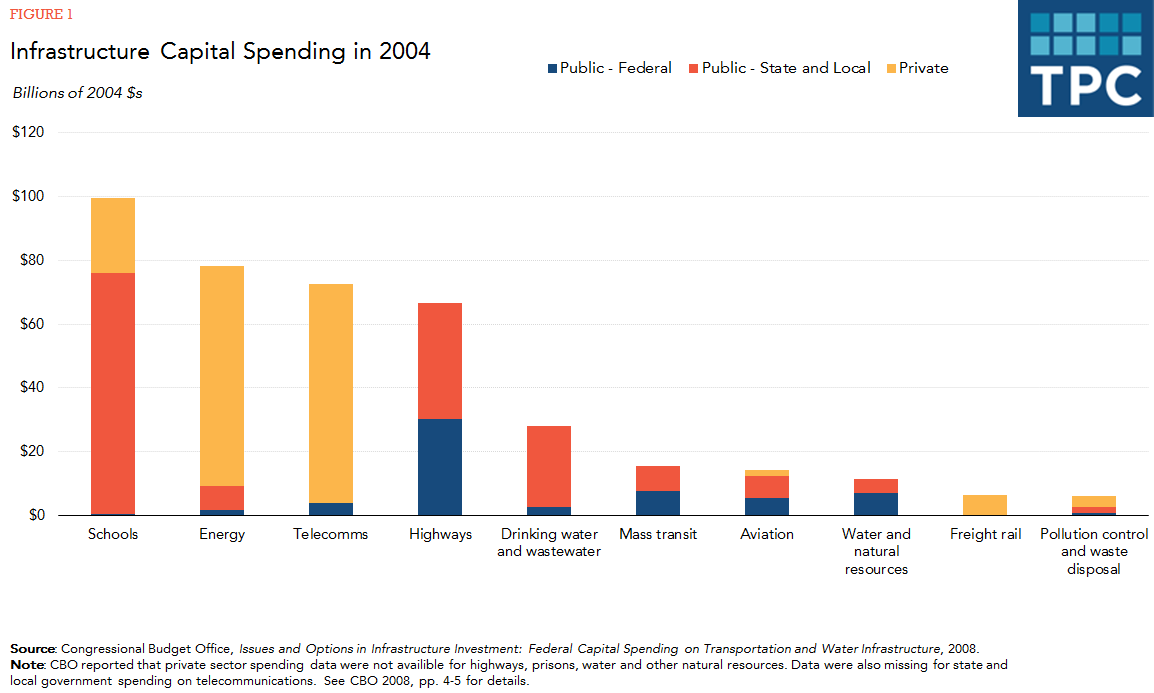

While it’s easy to get behind an “all of the above” strategy for rhetorical purposes, real-world investment decisions require hard choices, and some parts of our infrastructure lend themselves more to federal investment than others. For example, most US energy and telecommunications facilities are privately owned and operated, limiting the need for federal investment. Most drinking and waste water projects are funded by state and local governments with help from federal revolving loan funds as well as rate payments from users of those facilities.

Figure 1 illustrates how some forms of infrastructure are primarily funded by the private sector while others rely almost exclusively on public-sector funding. Although the data come from a decade-old Congressional Budget Office report, the same basic patterns apply today.

The argument for federal involvement in infrastructure is that states and localities may be unwilling to help pay for projects with broader regional and national benefits. However, beyond the interstate highway system, northeast corridor rail investments, and regional public transit, there may not be too many of these projects. And even with federal dollars on the table, governors may still say no.

Second, revenues are hard to come by. Congress has not increased federal fuel taxes (the Highway Trust Fund’s main revenue source) since 1993, even when gas prices were falling. As a result, Congress has had to transfer $140 billion in general revenues to the Highway Trust Fund since 2008.

In the past, the Trump Administration had taken an ecumenical approach to infrastructure funding – voicing support at various times for repatriated foreign earnings as well as tax credits, a national infrastructure bank, and even a federal gas tax hike. It has also called for streamlining regulatory approvals, privatizing air traffic control, and promoting public-private partnerships (P3s).

But enhancing private development of infrastructure is at odds with ending PABs, which have been involved in three-quarters of all P3s since 2005. The administration’s proposed FY2018 budget would also cut $2.4 billion in US Department of Transportation spending, including eliminating the popular TIGER (Transportation Investment Generating Economic Recovery) program, which allocates funds to localities on a competitive basis.

Trump aides promise that infrastructure will be the next big White House priority after tax reform. They’ve already indicated support for fast tracking projects of regional and national significance, especially those with state and local government or private revenue streams attached, and for encouraging states and localities to think about public assets as part of a strategic investment portfolio.

But that may be too little, too late. In any case, more creative thinking and more resources will be needed to address the country’s estimated $2 trillion infrastructure deficit.

Posts and comments are solely the opinion of the author and not that of the Tax Policy Center, Urban Institute, or Brookings Institution.

Tags

Julie Jacobson/AP Photo