Primary tasks

This year, Congress will consider what may be the biggest tax bill in decades. This is one of a series of briefs the Tax Policy Center has prepared to help people follow the debate. Each focuses on a key tax policy issue that Congress and the Trump administration may address.

What Is Infrastructure Spending?

Federal, state, and local governments spent $416 billion on water and transportation infrastructure in 2014, the most recent year comprehensive data are available. State and local governments spent $320 billion (77 percent), with the federal government providing the rest. This funding paid for highways, mass transit and rail, aviation, water transportation, water resources, and water utilities. It excludes capital spending on schools and prisons, as well as other utilities commonly funded by user charges and fees.

Of $416 billion, 40 percent went to highways, 26 percent to water utilities, and 16 percent to mass transit and rail (figure 1). State and local governments paid between 55 and 77 percent of transportation spending and funded nearly all water infrastructure.

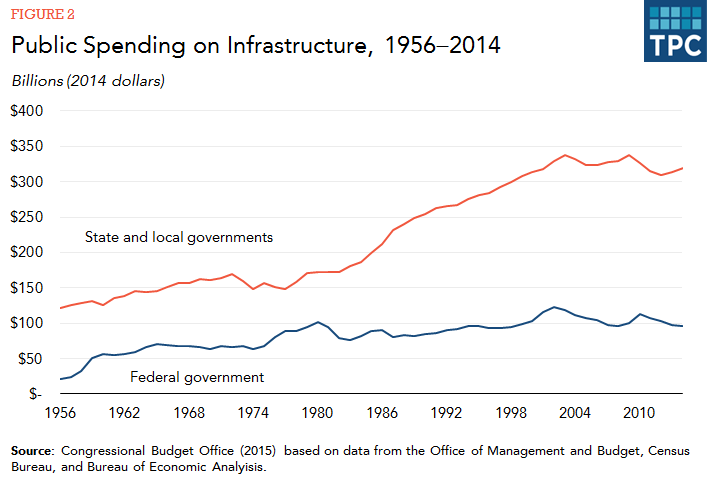

Real federal spending on infrastructure has changed little since the 1980s, so states and localities have had to spend more of their own funds on transportation and water (figure 2). Nonetheless, total infrastructure spending by all levels of government declined in real terms from $457 billion in 2003 to $416 billion in 2014, a drop of 9 percent.

While public spending has declined, the cost of building infrastructure in the US is relatively high. That cost depends on a combination of factors, including how many people might use the facilities and the cost of employing skilled workers for building or maintenance. These costs vary across states.

How Do We Fund Infrastructure Spending?

The federal government gets most of its dollars for roads and mass transit from the Highway Trust Fund (HTF). Funding for the HTF comes from user fees earmarked for transportation, such as the 18.4 cents per gallon gasoline tax and the 24.4 cents per gallon diesel tax. However, partly because Congress has not raised the gas tax since 1993, the fund’s revenue has consistently fallen short of spending over the past decade. In late 2015—after a decade without a long-term spending bill and 36 short-term extensions—Congress passed a five-year transportation bill authorizing future spending, but all funding was borrowed or transferred from the general revenue fund. This means the HTF will still face deficits when the bill expires.

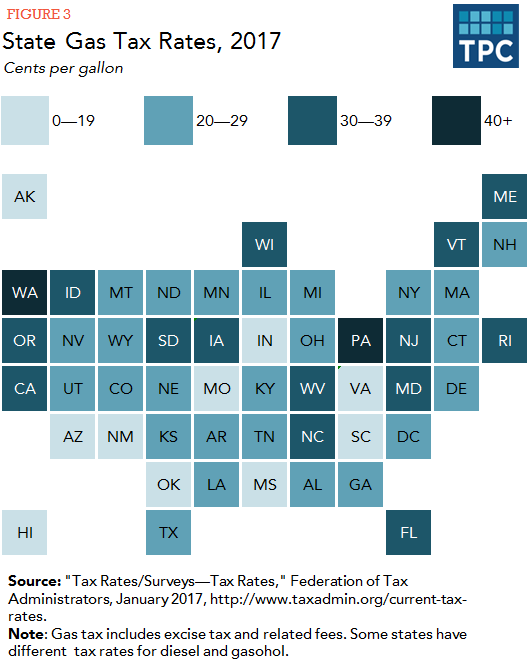

State governments also use motor fuel taxes primarily to pay their share for transportation projects. In 2017, state gas tax rates range from 9 cents per gallon in Alaska to 58 cents per gallon in Pennsylvania (figure 3).

Because both federal and state gas taxes apply to the volume of fuel purchased, tax collections have not kept up with inflation. Further, as Americans have purchased more fuel-efficient vehicles, consumption has fallen. As a result of eroding revenues, states have had to raise rates to maintain tax collections. While increasing gas taxes is politically difficult, demand for transportation spending and lack of adequate funds has induced 19 states and the District of Columbia to increase their gas taxes since 2013.

States have also found alternative sources of revenue to pay for transportation, including tolls, vehicle registration fees, and money transferred from other funds. Oregon has begun testing a vehicle miles traveled tax on fuel-efficient cars, to supplement the gas tax. In 2016, the federal government provided grants to Oregon and six other states to test alternative ways to increase highway funding.

Water utilities are funded primarily through user fees. State fees vary depending on spending, mostly because current fees must pay for both past and future large capital projects. While the federal government funded water utilities via grants in the 1970s and 1980s, that source has since fallen off. This leaves state and local governments as the main support for water utilities.

To finance capital projects, state and local governments issue bonds. Called municipal bonds or munis, they fall into two broad categories: general obligation bonds, secured by general tax revenue, and revenue bonds, secured by revenue from the project the bonds will finance. For taxpaying residents of the muni-issuing state, interest is generally exempt from federal and state income taxes. These tax exemptions usually allow state and local governments to borrow more cheaply than other debt issuers, such as corporations.

Domestic municipal securities represent approximately 9.4 percent of total debt securities, making them a small but important part of the US financial system. However, experts have raised some concerns about the efficiency and equity of using the federal exemption of state and local bond interest to encourage infrastructure spending. State and local governments receive only a fraction of the revenue the federal government loses to the exemption; much of the lost revenue goes to wealthy taxpayers whose tax savings exceed the interest they forgo. In addition, making interest from state and local bonds tax exempt changes the relative prices of federal, state and local, and private goods.

How Might We Reform Federal Infrastructure Spending?

During the 2016 presidential campaign, Donald Trump’s advisers proposed an infrastructure plan that would provide $1 trillion of new infrastructure spending. Instead of increasing direct federal spending, the plan called for the federal government to provide tax credits to private investors who engage in public-private partnerships. These firms would receive tax credits for helping the government manage the design and construction, operating, or financing of a project.

Public-private partnerships offer many potential benefits, including faster access to capital when states and localities are up against statutory or constitutional limits on their ability to issue debt. Evidence suggests that such projects may be completed sooner and at lower taxpayer cost.

Many details of the Trump plan remain unclear, however, including what (if any) role state and local governments would play. Further, public-private partnerships require a revenue stream (such as tolls); many initiatives that provide a large public good to all residents—such as wastewater projects—would not be supported by public-private partnerships.

Neither the Trump tax plan nor that proposed by House Republicans explicitly calls for eliminating the municipal bond exemption, nor do they discuss options for reform, including tax-credit bonds or expanded federal grants. However, both call for undefined curbs on tax breaks, which could target the exemption.

In addition, because both plans would lower tax rates, they would reduce the value of the exemption and thus increase borrowing costs for state and local governments.