Primary tasks

This year, Congress will consider what may be the biggest tax bill in decades. This is one of a series of briefs the Tax Policy Center has prepared to help people follow the debate. Each focuses on a key tax policy issue that Congress and the Trump administration may address.

The Trump administration and the House Republican leadership have proposed repealing both the state and local tax (SALT) deduction and the alternative minimum tax (AMT). AMT taxpayers cannot claim the SALT deduction. Because of the complex interactions between the two provisions, however, nearly all high-income AMT filers would pay more tax if Congress were to repeal the SALT deduction, and three-quarters of AMT filers would pay higher taxes if Congress were to eliminate both the AMT and the SALT deduction.

The State and Local Tax Deduction

About 30 percent of tax filers opt to itemize deductions on their federal income tax return, and nearly all who do deduct their state and local taxes. High-income households disproportionately benefit from the SALT deduction because they are more likely to itemize and pay more state and local taxes. Over 90 percent of returns filed by taxpayers with income above $200,000 claim the SALT deduction.

Further, because high-income households pay a higher federal income tax rate, they also save more in federal income taxes for each dollar of state and local taxes deducted: the deduction saves $35 in income tax for each $100 deducted by someone in the 35 percent tax bracket but only $15 for each $100 deducted by someone in the 15 percent tax bracket.

The Alternative Minimum Tax

The AMT, however, limits or eliminates the benefit of the SALT deduction for many high-income taxpayers. The AMT is a parallel income-tax system with fewer exemptions and deductions than the regular income tax and a narrower range of tax rates. Taxpayers potentially subject to the AMT must calculate their taxes under both the regular income tax and the AMT and pay the higher amount. State and local taxes are not deductible under the AMT, and that is a major reason why taxpayers pay the alternative tax.

The Tax Policy Center (TPC) estimates that 5.2 million taxpayers will pay higher taxes because of the AMT in 2017, and most will be high-income households. But because the top 39.6 percent rate under the regular income tax is higher than the 28 percent top statutory AMT rate, the highest-income households typically do not pay the AMT.

TPC estimates that about 29 percent of households with income between $200,000 and $500,000 will pay the AMT in 2017 (representing almost two-thirds of AMT taxpayers) as will 63 percent of those with income between $500,000 and $1 million (nearly one-fifth of AMT taxpayers). In contrast, only 20 percent of households with income above $1 million will pay the AMT.

The Alternative Minimum Tax and the State and Local Tax Deduction

Many recent tax-reform proposals, including the House GOP’s “Better Way” plan, would eliminate the SALT deduction. The overlap between the AMT and the SALT deduction might suggest that the loss of the deduction would not affect high-income AMT households. However, TPC estimates that about 84 percent of AMT taxpayers would see their taxes rise by an average of about $5,180 if Congress eliminates the SALT deduction (table 1).

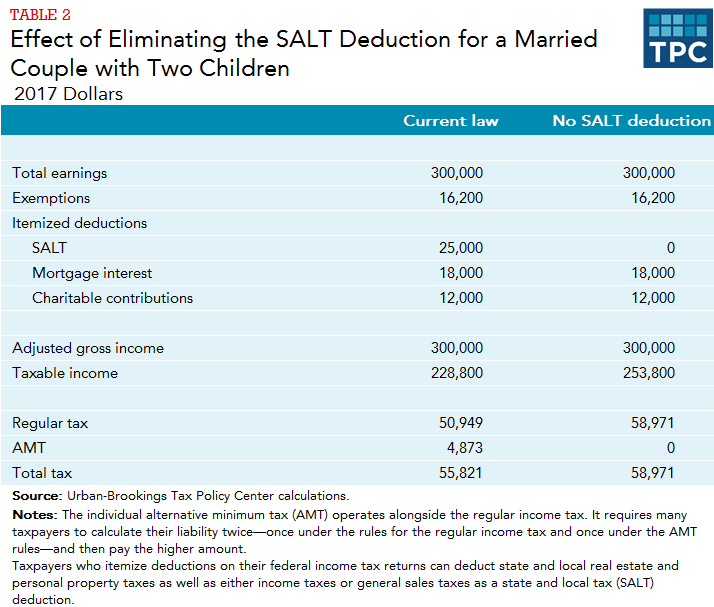

The reason may not be obvious, particularly to AMT taxpayers. Because their regular tax without the SALT deduction would be higher than their AMT, most AMT taxpayers in fact benefit from the SALT deduction even though they cannot claim it under the AMT. Consider the following example of a married couple with two children. The couple’s combined earnings are $300,000. They pay $25,000 in state and local taxes and claim deductions for mortgage interest and charitable contributions (both allowable under the AMT). Under current law, their regular tax liability is $50,949, but because their tax is higher when calculated under the rules for the AMT, they pay an AMT of $4,873 and total income tax of $55,821. If the SALT deduction were eliminated, their regular tax would jump to $58,971, but they would pay no AMT. Not paying the AMT would be small consolation for a higher overall income tax bill, especially because they would likely need to calculate their AMT liability anyway to see if they would be required to pay it.

If the SALT deduction were eliminated, an estimated 3.4 million taxpayers would fall off the AMT in 2017 (because their regular tax would exceed their AMT), leaving just 1.8 million taxpayers subject to the AMT.

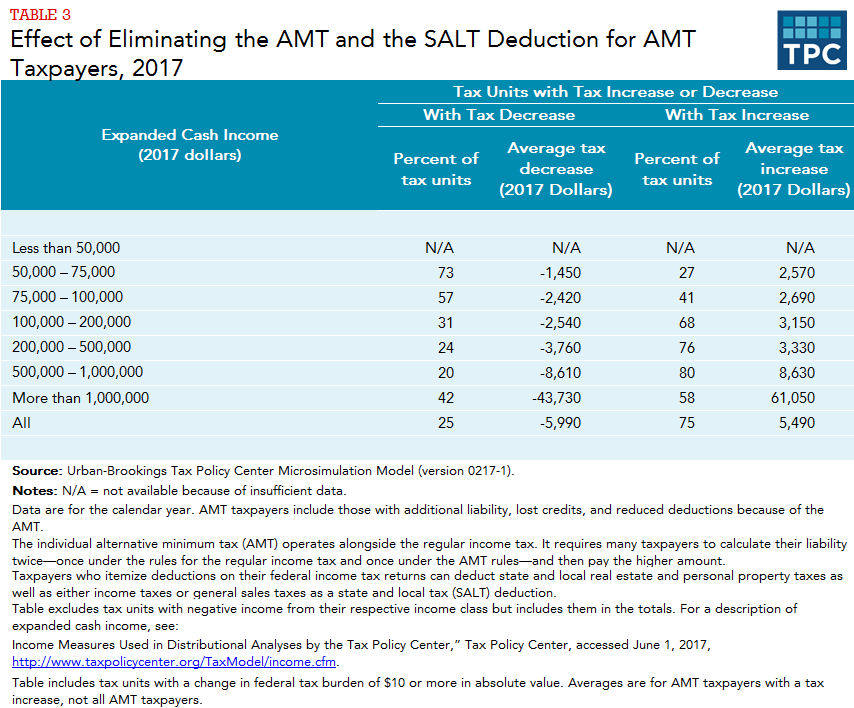

The House GOP plan and other tax-reform proposals would go even further and repeal both the SALT deduction and the AMT. However, TPC estimates that 75 percent of those now on the AMT would still pay higher taxes than under current law if both were repealed—their average tax increase would be $5,490. The remaining 25 percent of AMT taxpayers would see their taxes decline by an average of $5,990 (table 3).

The interactions between the AMT and the SALT deduction are complicated and not intuitive. Repealing the SALT deduction would raise taxes for most AMT taxpayers, and if the AMT itself was also repealed, about three-quarters of them would still see a net tax increase; the other quarter would receive a tax cut.