Primary tasks

This year, Congress will consider what may be the biggest tax bill in decades. This is one of a series of briefs the Tax Policy Center has prepared to help people follow the debate. Each focuses on a key tax policy issue that Congress and the Trump administration may address.

President Trump and congressional Republicans have proposed collapsing the seven individual income tax rates to three: 12, 25, and 35 percent. However, "The Unified Framework for Fixing Our Broken Tax Code", released in September, did not specify the income brackets to which the new rates would apply.

Current Income Tax Rates and Brackets

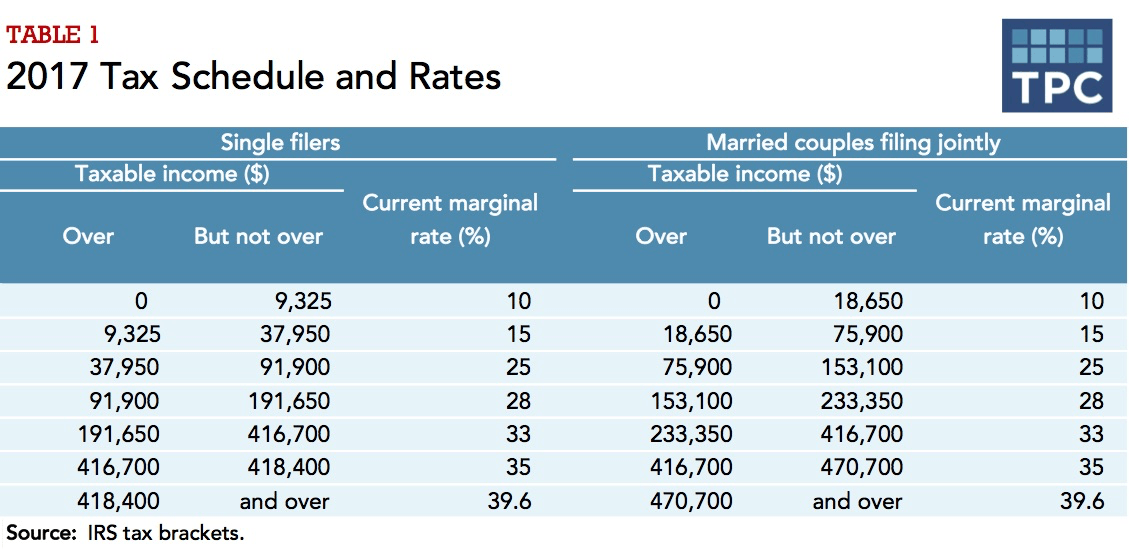

The federal individual income tax now has seven tax rates ranging from 10 percent to 39.6 percent (table 1). The rates apply to taxable income, a filers income subject to tax after exclusions and some adjustments (that is, adjusted gross income) minus deductions and exemptions.

Federal income tax rates are progressive: As taxable income increases, it is taxed at higher rates. Different tax rates are levied on different income ranges (or brackets) depending on the payers filing status. In 2017, the top rate (39.6 percent) applies to taxable income over $418,400 for single filers and over $470,700 for married couples filing jointly. Additional tax schedules and rates apply to taxpayers who file as heads of household and married individuals filing separate returns. Tax brackets are adjusted annually for inflation.

Today, nearly 80 percent of households are in the 15 percent bracket or lower—including those with no taxable income and those who do not file tax returns. Less than 1 percent of Americans earn enough taxable income to reach the current 33 percent bracket.

The Basics of Marginal Income Tax Rates

When you look at tax schedules and rates, always remember that each additional dollar you make is taxed at its marginal rate. If you earn enough to reach a new bracket with a higher tax rate, your total income is not taxed at that rate, just the income in that bracket. Even if you're in the top bracket, your first dollar of taxable income is taxed at the lowest rate (and so on through the tax schedule).

For example, a single filer with $50,000 in taxable income is in the 25 percent bracket but does not owe $12,500 in tax (25 percent of $50,000). Instead, he or she owes $8,238.75 (10 percent of $9,325 + 15 percent of $28,625 + 25 percent of $12,050).

The bottom bracket for married taxpayers is twice the size of that for singles, but the 25 percent bracket is e less than twice as large. That would cause a “marriage penalty” for some taxpayers in the higher tax brackets: some couples pay more tax filing a joint tax return than they would if each spouse could file as a single person.

Looming Federal Changes

The Unified Framework” would reduce the number of tax rates from seven to three: 12, 25, and 35 percent. The proposal allows for a possible fourth rate above 35 percent to ensure that the reformed tax code is at least as progressive as the existing tax code and does not shift the tax burden from high-income to lower- and middle-income taxpayers. However, the proposal did not specify the income ranges to which the rates would apply.

The House Republicans' 2016 "A Better Way" tax plan also used three rates (the top rate was 33 percent, though). Table 2 shows the tax schedule if the "Unified Framework" rates are applied to the income brackets in the "A Better Way" plan.

As shown, the 12 percent rate would apply to all taxable income below the 25 percent rate bracket. That means that income currently taxed at 15 percent would be taxed at a lower rate, but some income currently taxed at 10 percent would be taxed at a higher rate of 12 percent. However, the Unified Framework" would also raise the standard deduction, meaning that more income would be taxed at a zero rate for some taxpayers. How these changes would affect individual tax filers would vary based on filing status and family size (see our brief on the standard deduction and personal exemptions for more information).

Arguments for Reducing the Number of Tax Brackets and Lowering Rates

Supporters of lower rates make two main arguments. First, reducing the number of rates simplifies the income tax system. Having fewer brackets would help more filers know their marginal tax rates and thus make more informed decisions about work, charitable giving, and other matters that affect their federal income taxes. However, the individual income tax is complex mostly because it treats income from various sources differently and because it contains countless deductions and other special benefits, not because it has multiple tax rates. (Plus, most of us don't do our taxes by hand—about 90 percent of us either use computer software or hire someone to complete our returns.) Reducing the number of rates could be a part of a reform package, but eliminating preferences would be a far more significant step toward a simpler system.

Second, lower individual income tax rates may promote economic growth. The effect of income tax rate cuts on the economy is complicated. For example, lower tax rates on wages can increase incentives to work, but they can also make taxpayers feel richer and thus reduce incentives to work. Furthermore, lower tax rates can raise budget deficits if they aren't offset with spending reductions or paring back tax preferences. Higher deficits can reduce net national saving, increase interest rates, and depress economic growth.

History of Federal Income Tax Brackets and Rates

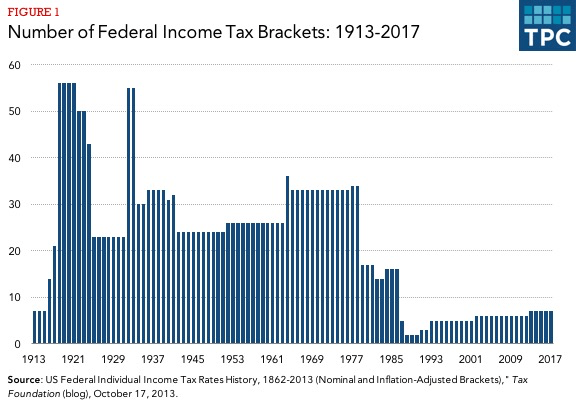

Over the 100-plus year history of the modern federal income tax (short-lived income taxes existed before the 16th Amendment), the number of brackets and rates has changed dramatically and frequently. The federal income tax began with seven brackets but that number exploded to more than 50 by 1920 (figure 1). From then until the late 1970s, we never had fewer than 20 brackets. The last major federal tax reform, the Tax Reform Act 1986, reduced the number of brackets from 16 to two, but that number has crept up to the current seven over the last three decades.

The top marginal federal income tax rate has varied widely over time (figure 2). The top rate was 91 percent in the early 1960s before the Kennedy tax cut dropped it to 70 percent. In 1981, the first Reagan tax cut further reduced the top rate to 50 percent, and the 1986 reform brought it down to 28 percent. Subsequent legislation increased it to 31 percent in 1991 and to 39.6 percent in 1993. George W. Bush’s tax cuts lowered the top rate to 35 percent, but it reverted to 39.6 percent when the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 let the reduced rate expire as scheduled.