How did the TCJA change the AMT?

The 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) included provisions that significantly reduced the impact of the alternative minimum tax (AMT). The TCJA enacted a higher AMT exemption, raised the income level at which the exemption begins to phase out, and repealed or scaled back some of the largest AMT preference items. As a result, TPC projects that the number of AMT taxpayers fell from more than 5 million in 2017 to just 200,000 in 2018.

The 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), included provisions that significantly reduced the impact of the alternative minimum tax (AMT). The TCJA enacted a higher AMT exemption and an increase in the income at which the exemption begins to phase out. It also repealed or scaled back some of the largest AMT preference items—personal exemptions, the state and local tax deduction, and miscellaneous deductions subject to the 2 percent of adjusted gross income floor—further limiting the AMT’s scope.

The AMT exemption for 2020 is $113,400 for married couples filing jointly, up from $84,500 before the enactment of the TCJA in 2017 (table 1). For singles and heads of household, the exemption rises from $54,300 in 2017 to $72,900 in 2020.

The TCJA dramatically increased the exemption phaseout threshold, which was $160,900 for married couples ($120,700 for singles and heads of households) in 2017. In 2020, the AMT exemption begins to phase out at $1,036,800 for married couples filing jointly and $518,400 for singles and heads of household.

Before the enactment of the TCJA, some of the larger AMT preference items included the deduction for state and local taxes (62 percent of all preferences in 2012 according to data from the US Department of the Treasury), personal exemptions (21 percent), and the deduction for miscellaneous business expenses (9.5 percent). Because the TCJA temporarily repealed the latter two provisions and capped the deduction for state and local taxes at $10,000, other preferences, such as the standard deduction and the special AMT rules for the treatment of net operating losses, depreciation, and passive losses, will become more important through 2025.

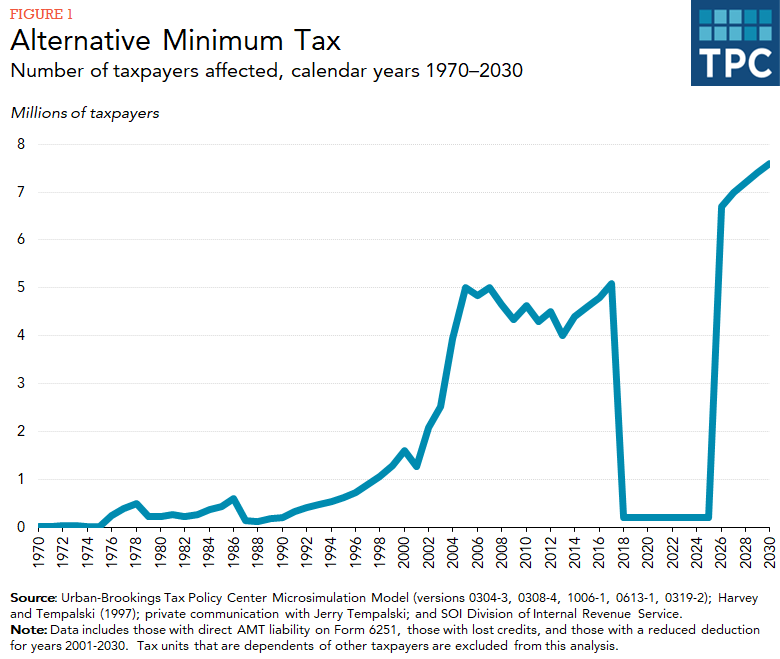

Primarily as a result of the changes enacted by the TCJA, TPC projects that the number of AMT taxpayers fell from more than 5 million in 2017 to just 200,000 in 2018 and will remain roughly constant through 2025 (figure 1).

The AMT provisions, along with almost all other individual income tax measures in the TCJA, are set to expire at the end of 2025. Thus, barring legislation from Congress, the AMT will return in force in 2026, affecting 6.7 million taxpayers. That number will rise to 7.6 million by 2030.

Updated May 2020

Internal Revenue Code, 26 USC.

Internal Revenue Service. 2019. “IRS Revenue Procedure 2019-44.”

Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center. “Microsimulation Model, versions 0304-3, 0308-4, 1006-1, 0613-1, and 0319-2.”

———. Table T20-0123. “Aggregate AMT Projections and Recent History, 1970–2030.”

Burman, Leonard E. 2007a. “The Alternative Minimum Tax: Assault on the Middle Class.” Milken Institute Review, October.

———. 2007b. “The Individual Alternative Minimum Tax.” Testimony before the United States Senate Committee on Finance, Washington, DC, June 27.

Harvey, Robert P., and Jerry Tempalski. 1997. “The Individual AMT: Why it Matters.” National Tax Journal 50 (3): 453–74.